By Carl Horowitz

This column was originally published in Townhall.

If ever a federal agency were a candidate for termination, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) would make for a good choice. The BIA combines patronage and ethnic separatism into a single package, wasting sizable tax dollars in the process. Yet few in Congress have the stomach for a fight with supporters of the bureau, now with a roughly $2.7 billion annual budget. That’s not the only Indian agency in need of serious downsizing.

The Bureau of Indian Affairs actually goes back nearly two centuries. Secretary of War John Calhoun virtually single-handedly created the BIA in 1824 to oversee treaty negotiations, conduct trade, establish budgets, and operate schools. In 1849, Congress moved the bureau from the War Department to the new Interior Department, where it since has been housed. In recent decades, the agency has become a conduit through which tribal leaders and their allies can accrue money and influence. It’s a variation on what public choice economists call “regulatory capture,†in which firms – especially large ones – effectively dictate policies and practices to the regulator, so as to maximize competitive advantage.

The current system is a by-product of periodic warfare beginning in the early-17th century and lasting through most of the 19th century. There are now 565 federally-recognized Indian (including Alaskan) tribes in this land of ours, representing nearly two million persons. Indian territories comprise some 55 million surface acres. Crucially, a tribe operates under a federal grant of sovereign status. Taken as a whole, Indian tribes are a loose confederacy of mini-nations, each with its own elected tribal government overseeing courts, schools, job training, health care, infrastructure development, and on due occasion, casinos.

Within their respective reservations, tribal leaders enjoy enormous power. Too often, they and employees use this power as a cover for corruption. Recent cases abound. At the Fort Peck Indian Reservation in northeastern Montana, for example, six office employees – two federal and four tribal – pleaded guilty last year to embezzling roughly $400,000 from a tribal credit program. In Oklahoma, Dawena Pappan, former secretary-treasurer for the Tonkawa tribe, pleaded guilty in federal court that year to stealing hundreds of thousands of dollars in casino proceeds with help from other Tonkawa officers.

Want more? Emily Anne Sauppity, secretary-treasurer of the Apache of Oklahoma, was found guilty by a federal jury of embezzling $46,068 in oil and gas royalty taxes, though her actual thefts amounted to nearly $108,000. Evelyn James, former president of the San Juan Southern Paiute Tribe in Arizona pleaded guilty to theft and money-laundering of nearly $300,000 in Justice Department community policing funds. And about a dozen persons, including two former tribal officials, pleaded guilty or were found guilty in Oklahoma City federal court to embezzling about $750,000 from the Lucky Star Casinos, operated by the Cheyenne and Arapaho of Oklahoma.

It isn’t just Bureau of Indian Affairs funds that have made their way into the pockets of crooks. In mid-2008, for example, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) issued a report revealing that the Indian Health Service (IHS), part of the Department of Health and Human Services, during fiscal years 2004-07 “lost†about 5,000 pieces of medical equipment with an acquisition value of $15.8 million. In a follow-up evaluation audit released in June 2009, the GAO noted: “IHS continues to lose property at an alarming rate, reporting lost or stolen property with an acquisition value of about $3.5 million in a little over a year…†Missing items included a $170,000 ultrasound unit, a $100,795 mammography X-ray machine, and various dental chairs and diagnostic monitors.

Far bigger piles of loot, however, can be made legally. Class-action lawsuits are one route. Over the past few months, Indian plaintiffs and their attorneys managed to coax massive settlements from the federal government in two longstanding unrelated civil suits. Last October, lawyers for tens of thousands of Indians corralled a $760 million agreement from the U.S. Department of Agriculture as compensation for credit discrimination against Native American farmers and ranchers. Known as Keepseagle v. Vilsack and originally filed by a Sioux couple in North Dakota in 1999 as a copycat of the Pigford (i.e., “black farmerâ€) lawsuit, the case did not uncover any specific acts of willful discrimination. In the other lawsuit, Congress in November created a $3.4 billion trust fund to be shared by an estimated 300,000 to 500,000 Indians, pursuant to the settlement in Cobell v. Salazar, in which the plaintiffs had alleged that the Interior Department for decades had squandered royalties due individual Indians for extracted oil, gas, timber and other natural resources from tribal lands. The details of the case suggest a well-planned and executed plaintiff shakedown.

An even bigger street-legal money maker is casino gambling. In 1988, Congress enacted and President Reagan signed the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act (IGRA), which recognized “the right of Indian tribes in the United States to establish gambling and gaming facilities on their reservations as long as the states in which they are located have some form of legalized gambling.†This legislation effectively conferred monopoly rights upon a tribe to operate a casino on its property, subject to regulation by the National Indian Gaming Commission. These enterprises are immune from state regulation. Moreover, they are exempt from federal income taxation, though state governments may tax a portion of slot machine revenues.

Currently, some 220 recognized Native American tribes operate a combined roughly 400 Class I, II and III (casinos fit under the latter category) gaming facilities. Given the seemingly limitless capacity of Americans to place wagers, this has meant big bucks. The Foxwoods Resort Casino in southeastern Connecticut, owned by the Mashantucket Western Pequot Tribal Nation, thanks to several expansions, has become the largest hotel-casino complex in the U.S. Featuring 7,200 slot machines and 380 table games, the luxury facility takes in roughly $1.5 billion annually from combined gaming and non-gaming sources. Right down the road is the nation’s second largest casino venue, the Mohegan Sun Resort & Casino. Owned by the Mohegan tribe, this high-end getaway destination features 300,000 square feet of gaming space within three casinos. The Pechanga Resort and Casino in Temecula, California isn’t exactly small time either, containing 200,000 square feet of gaming space and 3,400 slot machines.

All told, Indian gaming in 2009 took in $26.5 billion in revenues. This represents an explosive increase from $100 million in 1988, the year of IGRA passage.

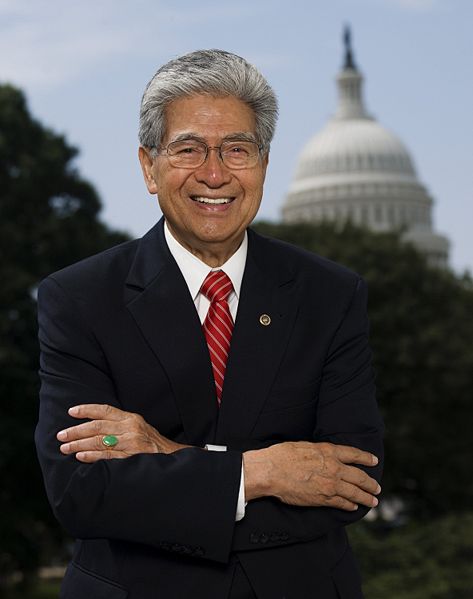

Someone out there is getting rich. And it isn’t just tribal leaders and outside investors. Tribes operate with a grant of monopoly privilege. Remaining shielded from competition requires gaining access to federal and state legislators to vote the right way. That’s where lobbyists come in. The 2006 final report of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, chaired by John McCain, R-Ariz., revealed that Jack Abramoff, though an extreme example (hence, the superficially satisfying cliché, “disgraced lobbyist Jack Abramoffâ€), was part of a larger “come and get it†political culture. A former BIA official, Wayne Smith, grandson of a Sioux chief, explained to CBS News at the time: “I had lobbyists…tell me that ‘It was our time, this is our time to make some money in the Indian game arena. We worked hard to get this president elected, and we expect to be rewarded for it.’†What matters here is that influence-buying is a product of tribal sovereignty and monopoly privilege. “Lobbyists†– love them or hate them – will always be around to service an Indian client’s political needs under this scenario.

If all this theft and influence-peddling amounted to nothing more than a few anecdotes, it would be easy to minimize their importance. Such behavior can be found in any type of organization, whether government agencies, corporations, unions, philanthropies or churches. Yet these cases, in fact, represent a fraction of widespread criminal and otherwise ethically-challenged activity. It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the system of tribal governance, with an able assist from Washington, is dysfunctional.

Bureaucratic client capture offers a partial explanation for this state of affairs. The ultimate problem is the setting aside of territory and public funds to accommodate Indian “nations.†Indian identity politics, at bottom, is about irredentism – the condition of two or more ethnic, linguistic or religious groups claiming sovereignty over the same territory. Many Indians have a deep attachment to ancient lands they believe were stolen by the white man. The federal government can’t bottle up their sense of moral entitlement. But it doesn’t have to subsidize it either.

Despite our best efforts, separatism and corruption appear to have become more pronounced over the past few decades. The late Sixties and early Seventies witnessed the aggressive rise of Indian identity politics, culminating in passage by Congress of the Indian Self-Determination and Educational Assistance Act (1975) and the Indian Child Welfare Act (1978). Lawmakers further encouraged decentralization of authority in 1991 with the Tribal Self-Governance Demonstration Project Act. With larger budgets and fewer strings attached, opportunities for corruption have increased, especially as the BIA itself has come to be heavily staffed by Indian activists.

Ending the network of incestuous relationships and accompanying corruption requires that Congress do the unthinkable: Abolish the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the Indian Health Service and all other federal agencies that serve Native American interests. These agencies have outlived whatever usefulness they had. Lawmakers also ought to end the practice of formal tribal recognition. Why should Cheyenne, Choctaw, Mohawk or Sioux sovereign “nations†exist within our borders, any more than Dutch, Irish, Italian or Polish ethnic ones? It is one thing for members of a particular tribe to live in close proximity, preferring their own company. It is entirely another for Americans as a whole to be coerced into subsidizing this tribal confederacy, an arrangement that is not only costly, but also corrosive of national identity.

Back in the late 1940s, Congress set up a commission on executive branch reorganization, chaired by former President Herbert Hoover. Among its hundreds of recommendations, the Hoover Commission concluded that assimilation of Indians into the mainstream of American society must be a top priority. More than six decades later, our nation remains a long way from realizing that goal. Dismantling the Indian bureaucracy would be a major step in that direction.

Carl F. Horowitz is director of the Organized Labor Accountability Project of the National Legal and Policy Center, a Townhall.com Gold Partner organization dedicated to promoting ethics in American public life.